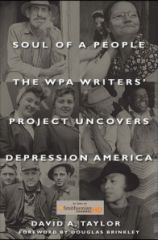

David A. Taylor is the author of Ginseng, the Divine Root: The Curious History of the Plant That Captivated the World, and a collection of short stories, Success, released just last year. His latest book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America, looks back at the Federal Writers’ Project, an initiative that at one point employed as many as 7,500 people and whose most lasting work was a series of guidebooks to U.S. states and cities. The WPA guides, or as they were originally known, the American Guides, sought to “hold up a mirror to America,” capturing the characters of places and people in ways that remain informative even today.

David A. Taylor is the author of Ginseng, the Divine Root: The Curious History of the Plant That Captivated the World, and a collection of short stories, Success, released just last year. His latest book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America, looks back at the Federal Writers’ Project, an initiative that at one point employed as many as 7,500 people and whose most lasting work was a series of guidebooks to U.S. states and cities. The WPA guides, or as they were originally known, the American Guides, sought to “hold up a mirror to America,” capturing the characters of places and people in ways that remain informative even today.

In Soul of a People, Taylor in turn captures the character of the project itself — the exciting and hopeful sense of mission, the often dreary bureaucracy behind the scenes, the increasingly harsh criticisms leveled against the endeavor as a whole — and offers profiles of the writers who found themselves on the WPA payroll, in many cases writers well-known today as novelists, poets and nonfiction masters.

The book is part of a larger program that will include a documentary to be aired later this year on the Smithsonian Channel and an extensive nationwide project sponsored by the American Library Association. While the book is available now, a formal launch party is planned for Tuesday, April 28, at 3 p.m. in the Mumford Room of the Library of Congress’ Madison Building. The public is invited.

In advance of all that, Taylor took part in an interview here about his new book, about the WPA guides themselves, and about what all of it can offer to today’s audiences.

Art Taylor: Soul of a People began as an article for Smithsonian, “A Noble and Absurd Undertaking,” first published 9 years ago this month. What prompted you to want to explore this subject as a book-length project? And what’s the most interesting or important thing about the WPA Guides and their writers that you learned from writing the book that you didn’t know/understand after completing the article?

David A. Taylor: Doing the article, I realized that trying out the WPA guides on the road in Nebraska only piqued my interest about the people who wrote them. I knew that there were counterparts to Rudy Umland, the hobo-turned-editor of the WPA guide to Nebraska, across the country. Working on the book, I found them and where their stories intersected. Umland, in fact, came to know the editor of the New Orleans guide, a novelist too. And the poet Weldon Kees, also from Nebraska, crossed paths with young Kenneth Rexroth and John Cheever, and Margaret Walker meeting Ralph Ellison by way of Richard Wright. So you start to see a dynamic among young writers at that time, who were learning reporting and writing skills and eking out a wage during the hard time, and finding a social and creative network through the WPA. It connected them with other seekers. It was a much bigger story.

What I learned by finishing the book was how varied that experience was for each of them. For May Swenson, coming out of a remote Utah family of immigrants and getting a WPA writer job in New York where she met veteran screenwriter and immigrant Anzia Yezierska, it was liberating. For Eudora Welty, working as a publicity assistant in Mississippi, the WPA job was sort of a novelty where she first started on stories. For Cheever, it was no great opportunity. For Zora Neale Hurston, it was something she kept private because it was basically a welfare job for an author who had published several novels and books of folklore, as she had done. Going through their journals and correspondence and biographies, and retracing some of their travels, I got to feel that range of experiences. As a writer, it’s fascinating to see how other writers vary so much in their abilities at making a life.

You mention Cheever, Ellison, Hurston and Welty. In those cases and throughout Soul of a People, the writers you profile will often be well-known to readers today. Did a large percentage of those WPA hires go on to become successful writers? And what can you tell us about the participants who simply put down their pens later or maybe never considered themselves writers at all?

I don’t think anyone has analyzed what percentage became successful. First, you’d have to agree on how you define success. Working at a local paper, writing book reviews for the Kansas City Star the way Umland did, could count as success, though he held himself to a tougher standard. You had many WPA writers who had never thought of themselves as writers yet who went on to publish books about historical figures (like Ruby Wilson did in Nebraska), or memoirs (like Hilda Polacheck did in Chicago), or historical investigations (like Juanita Brooks’s book about a 1800s massacre in Utah). I loved those stories because they clearly were working out of passion for the work – they weren’t getting famous from it.

Some of them did put their pens down when they left the FWP, maybe even most. And that made them harder to track down. But some who didn’t become professional writers left behind more thorough accounts of that time than others who did. Many had lots of incentive not to talk about their time as WPA writers again, since it became stigmatized, first as welfare and then as commie. A person like Stetson Kennedy in Florida, who got fired up by his FWP experience of revealing local histories and injustice regardless of how unpopular it was, that was rare.

In conjunction with your own trip to New Orleans, you write that you initially considered the WPA guide to that city a “dead relic” and then discovered how it “got inside the place and made it fascinating.” From your research, what aspects of the guidebooks in general seem most dated and what aspects retain their freshness? In short, to what degree is the portrait of America presented by the guides then still a valid portrait of America now?

It really varies from guide to guide. Some parts that you wouldn’t expect to have any life are interesting because of what has changed: radio stations, transportation, food and lodging – the texture of daily life. On the other hand, calendars of annual events, which I’d expect to have become obsolete, contain some traditions that keep on going. Some of the essays on ethnic composition and histories are the most out-of-date and strike us now as offensive. They tend to be best where they focus on individuals, or on local histories of pockets of dissent or separatism. Bernard Weisberger did a fine job of rounding up a sampling of the brightest nuggets in his WPA Guide to America.

A little bit of a follow-up: Comparisons between the Depression and today’s economy are sprouting up regularly in newspapers, in magazines, in daily conversation. On the basis of your readings in these books and the stories you’ve uncovered about these writers, what parallels stand out in your mind? Or, alternately, what evidence stands out to refute those comparisons?

It’s interesting – in terms of the stages of recognizing the problem, our national psychology seems remarkably durable. We react the same way to huge losses now as then – train-wreck headlines, private denial, debate, attempts at emergency action. There are also a lot of parallels in knee-jerk reactions against immigrants (“taking American jobs”) and debates about types of jobs are “essential.”

On the other hand, we’re looking at unemployment rates now of about 8 or 9 percent, less than one third as bad as during the Depression. Plus, that one was nearly five years deep when the WPA got started; ours is expected to end in a year. It’s just a completely different scale of problem.

The book you’ve written is part of a larger project, including the Smithsonian Channel film and the American Library Association’s outreach programs. I was particularly interested to see that the ALA’s Soul of a People website encourages, in part, the “informal taping of local people’s memories and accounts of present-day lives (in the style of the Writers’ Project and using interview guidelines used by the FWP).” How do you personally hope that building awareness of the WPA Guides might help to spark a new look at who we are, where we came from, and where we live?

At a workshop of the librarians and scholars funded by the ALA grants, I was fascinated to hear all the ideas they were exploring for the programs. It’s too early to say how they’ll do because they haven’t happened yet (most will happen this summer and fall), but discussions, for example, of a local WPA guide’s portrayal of their community – whether it was ever accurate, whether it was before but essentially changed – should be fun to track.

The Soul of a People film, directed by Andrea Kalin, will be screened at those library events too, and I can’t wait to see how people respond. We were lucky to have people who worked for and against the FWP and their family members, and some great commentators. The divisions in America of that time that you see in the film are still with us, and reflect a real mixed – and probably a stronger overall – group identity.

Finally, are the questions about places and their people asked by the WPA guides — where do we live? where did we come from? who are we? — being explored and answered today by newspapers, magazines, nonfiction books, novels, etc. in a spirit similar to (or even inspired by) those guides? And if so, is the possibility of a comprehensive portrait of America today within our reach or beyond our grasp?

We have a lot more channels for communicating about who we are today than people did in the 1930s. And frankly, we have more time for it. But more importantly, I think, there’s a more widely shared sense of valuing the stories of people beyond those who “influence the course of history.” We want to know what the world felt like from a lot of perspectives. I think the FWP had a much greater influence in that democratic view than we typically realize. The current interest in oral history – things like StoryCorps and intergenerational interviews that schools assign students to do – grew out of the Federal Writers’ Project and particularly the work of Ben Botkin, its folklore director. Botkin widened the field of folklore – he called it “living literature that doesn’t get captured on the page.” Many academics of his time resisted that move toward social history, but looking at history from the ground up has much more currency now.

At the same time, you see channels that lasted generations now hitting the rocks, including some you mention – newspapers, magazines, even novels. So we may have a more multifaceted lens – like an insect’s compound eye – for making such a “comprehensive portrait,” but maybe less faith that there’s a comprehensive brain behind those eyes capable of absorbing it. If that makes sense. Developing that brain may be the next growth area.

Pingback: N.C. Events: Taylor, Southern, and Dessen & Smart Bitches On Heaving Bosoms « Art & Literature

Pingback: A Long Week…. « Art & Literature

Pingback: Q&A With David A. Taylor, Soul of a People « Mark Athitakis’ American Fiction Notes

This is a great interview–I look forward to reading the book AND seeing the documentary.

Pingback: David A. Taylor Discusses Soul of a People « Art & Literature | NonFictionArea.Com